The list of fallacies relevant to argument includes one that isn’t, strictly speaking, a fallacy under all circumstances: the “argument from authority.”

If we read authority to mean expert status, there is a place for it in arguments over substantive matters. Problems with expertise-based arguments arise in two venues:

- The validation of the claimed expertise;

- Its position in the priority scheme of argumentation methods.

If the above seems a bit too abstract, commenter Zachriel at Bookworm Room has provided a compact elucidation:

An appeal to authority is a type of inductive argument {eta: based on the experience that experts are more likely to be correct than non-experts in a field, though not infallibly so} and is evaluated as follows:

- The cited authority has sufficient expertise.

- The authority is making a statement within their area of expertise.

- The area of expertise is a valid field of study.

- There is adequate agreement among authorities in the field, and the authority is expressing this agreement.

- There is no evidence of undue bias.

The proper argument against a valid appeal to authority is to the evidence.

Excellent – and vitally important to contemporary arguments over all sorts of matters. There is a priority order to valid forms of argument. Expertise has value, if it’s authentic and founded on prior demonstration. However, it has less value than evidence. Evidence trumps everything else – and a true expert will always concede that.

Let’s get back to my Problem #1 for a moment. It bears directly on Zachriel’s exposition on authority / expertise. How does one validate a proposed authority’s expertise sufficiently to make his arguments worth considering?

Well, first off, we should avoid those darlings of the talk shows, the Anything Authorities:

Virtually everyone is touched at some point by the arrogance of an expert. I have to saw one in half about once a month, but for a reason tangential to Ace’s analysis: their readiness to assert “expertise” in fields other than their own. Arthur Herzog skewered this tendency in his 1973 classic The B.S. Factor:

The thirst for answers in a difficult world has brought about the rise of Anything (or Everything) Authorities. The Anything Authority is one whose credentials in one field are taken as valid for others — sometimes many others….

The trouble with an Anything Authority is not that he takes a position or works for a cause, but that he seldom seems to apply the same standards of research and documentation to the field in which he is not an expert as he would to his own….

Psychiatrists are a special breed of Anything Authorities because their field is anything (or almost) in the first place….

When an Anything Authority becomes successful, he joins the Permanent Rotating Panel Show and appears on television programs, which pay him….the Anything Authority must never be stuck for an answer. Glibness helps, and so does the fact that many emcees do not know the hard questions to ask.

If the above passage has you thinking of Fox News regular Dr. Charles Krauthammer, you’re not alone.

The progression is plain:

- Acquisition of a credential of some kind, often an academic one.

- Practice in one’s field.

- Acquisition of notoriety in consequence of some publicized event.

- Interest in one’s thinking from persons other than one’s fellow specialists.

- Increasing boldness, in part due to sustained attention from laymen and journalists.

- Ascent to Anything Authority status.

- Television gigs and book tours.

The strong relationship between the Anything Authority and major figures in national politics follows automatically.

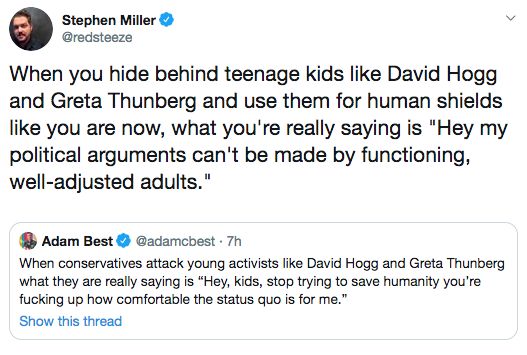

But that’s only one end of the spectrum. We must also take care to ignore the Nothing Authority:

What lies between those two extremes?

I was once deemed an expert of sorts. My field was real-time software, and I was respected at it. But expertise in engineering has a special set of characteristics: it involves prior achievements that are beyond dispute. In other words, you can see, hear, and feel it.

Engineering is the discipline that solves problems by applying physical knowledge and /or existing technology. When engineers argue, their expertise is counted to a certain extent and no further: what has worked in the past. Such expertise is discounted when considering new methods made available by subsequent technological advances. Of course, those new methods must prove themselves in the crucible of application, but that’s where we enter the realm of evidence.

Expertise in any of the realms of knowledge that don’t involve problem-solving – e.g., physics, chemistry, astronomy, et alii — is founded on prediction. To establish oneself as an expert requires a series of successful predictions: the use of the knowledge one has claimed to create a demonstrable connection:

- From a specified context;

- Affected by a specified stimulus;

- To a consequence that arrives at a specified time.

Once again, I have the pleasure of citing the late Sir Fred Hoyle’s novel The Black Cloud:

“It looks to me as if those perturbations of the rockets must have been deliberately engineered,” began Weichart.

“Why do you say that, Dave?” asked Marlowe.

“Well, the probability of three cities being hit by a hundred-odd rockets moving at random is obviously very small. Therefore I conclude that the rockets were not perturbed at random. I think they must have been deliberately guided to give direct hits.”

“There’s something of an objection to that,” argued McNeil. “If the rockets were deliberately guided, how is it that only three of ’em found their targets?”

“Maybe only three were guided, or maybe the guiding wasn’t all that good. I wouldn’t know.”

There was a derisive laugh from Alexandrov.

“Bloody argument,” he asserted.

“What d’you mean, ‘bloody’ argument?”

“Invent bloody argument, like this. Golfer hits ball. Ball lands on tuft of grass — so. Probability ball landed on tuft very small, very very small. Million other tufts for ball to land on. Probability very small, very, very very small. So golfer did not hit ball, ball deliberately guided onto tuft. Is bloody argument, yes? Like Weichart’s argument….Must say what damn target is before shoot, not after shoot. Put shirt on before, not after event.”

The prediction must come before the consequence to be predicted! Anyone can say “Just as I predicted!” after the event occurs. That doesn’t take knowledge, only a lot of gall.

Concerning the claims of expertise submitted in the political arena, the majority aren’t even worth committing to paper so we could have the fun of shooting them full of holes. The persons making arguments from authority:

- Lack sufficient expertise;

- Are outside any area of expertise they might validly claim;

- Their field, if any, is not a valid field of study;

- There is no agreement among authorities in that field;

- They’re demonstrably biased.

That final point is the most telling of all: When their claims are contradicted by the evidence, they dismiss the evidence. Indeed, some of them have taken to hiding the evidence to protect their claimed “expertise”…and, of course, the benefits that flow to them from their assertions of “authority.”

A genuine expert, who possesses the self-respect that comes from demonstrable accomplishments, would never do such a thing. As we mathematical types like to say, quod erat demonstrandum.

I could go on about this. History is filled with examples of “experts” who did all manner of contemptible things to protect their stature as such. The one that comes to mind most readily is Trofim Lysenko. But there have been many others.

Remember always:

When evidence is available,

The true expert will defer to it.

All else is vanity.