“Say, what if there were no hypothetical questions?” – Originator unknown

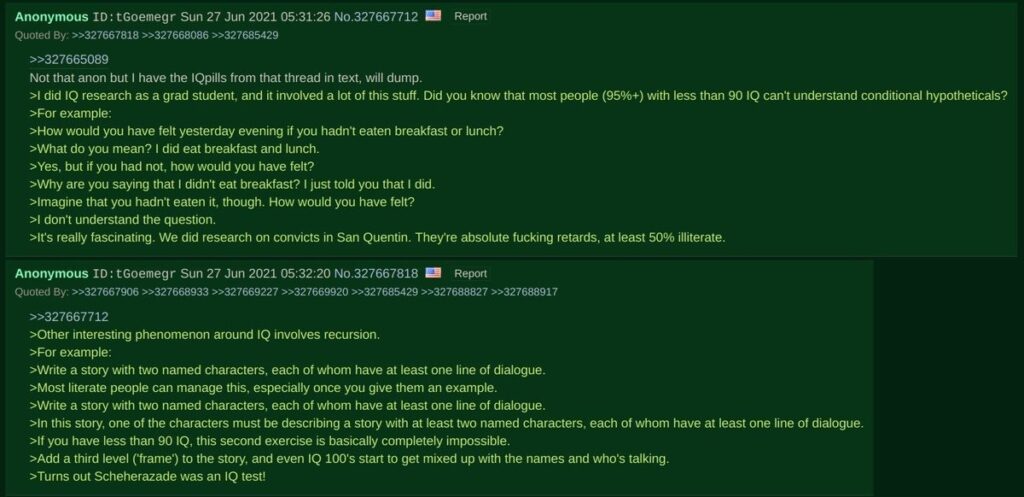

I found this at Ace’s place:

I can’t speak to whether the figures cited are accurate. However, the suggestion that persons of below-average intelligence would have trouble understanding such propositions seems like that most uncommon of all things, “common sense.” Moreover, when a hypothetical is buried two or more layers deep, such that it occupies a “nested fantasy” universe, I’d imagine even bright people would have some difficulty with it. It requires the patient, accurate operation of mechanisms most people don’t possess, much less exercise regularly.

And it bears directly and heavily on storytelling.

I use the technique called “framing” – the embedding of the “main” story within a “frame” story whose action and dialogue occur later in fictional time – fairly often. I employed it in Chosen One, Polymath, Statesman, Love in the Time of Cinema, Antiquities, and The Warm Lands, and I feel it served my purposes well. But it can be confusing if done poorly.

Formatting the “frame” segments to distinguish them from the “main story” segments, which is my approach to maintaining clarity, can help the reader to keep the two timelines separate. Other writers prefer other methods. But however one goes about it, any deviation from regularity in treatment can produce an incomprehensible mess.

Now imagine that in a tale structured that way, one character within the “main” story tells an extensive “inner” story to an interlocutor. Imagine further that the “inner” story contains a dialogue between two persons, one or both of whom appear in the “main” story. Can you see the difficulties the reader would face in keeping the timelines and events properly segregated?

It can get worse, of course. Imagine that within the “inner” story, one of the “main” story characters proposes hypothetical questions to another – questions that bear indirectly on what happens in the “main” story. At this point, the reader is struggling to separate what’s happened in the various timelines and to what extent those “inner” story hypotheticals, and the conditions on which they’re based, drive the events in the “main” story.

I’ve never done such a thing, and I hope never to feel an irresistible urge to do so. I don’t know of any popular writer who’s done it, either. It would make the hash some storytellers make of their verb moods and temporal referent language appear simple and clear by comparison.

Add it to the list of pre-anathematized practices all storytellers should avoid. Complexity for the sake of describing truly, unavoidably complex events is forgivable; enmeshing your reader in a maze of timelines, hypotheticals, and conditional propositions that require a CPM chart to keep straight is not.

1 comment

Given I have enjoyed each of those and didn’t seem to have difficulty with them, well, I guess it means something.I was talking to someone in the last week about movies that have two or more timelines and that jump back and forth between or amongst them and how most people get too confused to follow and consider the movies junk. I actually LIKE such because it makes me organize the story in my head.As to the conditionals, maybe it is why my writings have had limited interest. Asking someone to step out of their frame of reference exceeds many people’s capacity. I get context matters, but how else are you expected to understand ANYONE that comes to different conclusions?