This might prove to be the start of a series of essays. Beneath every argument about anything whatsoever, there will lie a question that must be answered for the argument to be soluble:

That question, of course, must become specific for it to be relevant and to have substance. It’s about defining the subject being discussed: giving it adequately firm boundaries to allow the participants to require what’s necessary and to exclude what’s irrelevant. When such boundaries are agreed upon a priori, a great many thrusts that occur within the argument can be dismissed as meaningless or worse. Without them, resolution is impossible.

A few moments’ thought about that necessity clarifies the import of the Left’s habit of asserting irrelevancies and insisting upon their relevance. But that’s a subject for another tirade.

Roger Kimball is one of my favorite contemporary essayists. Whatever he has to say always has substance and heft. This piece at American Greatness is typical of his output. Yet this time around, he exhibits a certain frustration about his subject. That’s understandable, for the subject is art, and the frustration about what it is has a centuries-long history.

One of Kimball’s observations struck me with particular force:

We suffer today from a peculiar form of moral anesthesia: an anesthesia based on the delusion that by calling something “art” we thereby purchase for it a blanket exemption from moral criticism—as if being art automatically rendered all moral considerations beside the point.

He cites George Orwell in concurrence:

The artist is to be exempt from the moral laws that are binding on ordinary people. Just pronounce the magic word ‘Art,’ and everything is O.K. Rotting corpses with snails crawling over them are O.K.; kicking little girls in the head is O.K.; even a film like L’Age d’Or [which shows, among other things, detailed shots of a woman defecating] is O.K.

Moral criticism, of course, isn’t the only sort. One who looks upon something proposed as “art” will typically have several considerations in mind: accuracy, aesthetics, and relevance among them. Some great art has been produced from great horrors; I have in mind in this connection much art that emerged from World War I, which depicted corpse-strewn battlefields and formerly verdant forests destroyed by artillery. But Kimball’s and Orwell’s observations generalize handily…at least for those willing to ask the critical question.

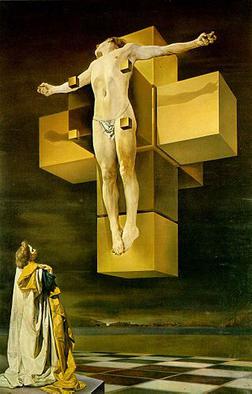

The word art is a battlefield all by itself. Its main use in discourse is as a term of exemption from standards, as Kimball and Orwell have told us. But opinions vary about the praiseworthiness even of some things widely acclaimed as great art. Consider this Salvador Dali painting:

Christ crucified on a floating tesseract? Above a checkerboarded field? No “INRI” above His head? No thieves to either side? No gaggle of Roman soldiers jeering up at Him? It’s a widely acclaimed painting, but for what? What does it show us that deserves applause? Imagination? Technique?

Once again I am reminded of a passage from C. S. Lewis’s That Hideous Strength:

There was a portrait of a young woman who held her mouth wide open to reveal the fact that the inside of it was thickly overgrown with hair. It was very skilfully painted in the photographic manner so that you could almost feel that hair; indeed you could not avoid feeling it however hard you tried. There was a giant mantis playing a fiddle while being eaten by another mantis, and a man with corkscrews instead of arms bathing in a flat, sadly colored sea beneath a summer sunset. But most of the pictures were not of this kind. At first, most of them seemed rather ordinary, though Mark was a little surprised at the predominance of scriptural themes. It was only at the second or third glance that one discovered certain unaccountable details—something odd about the positions of the figures’ feet or the arrangement of their fingers or the grouping. And who was the person standing between the Christ and the Lazarus? And why were there so many beetles under the table in the Last Supper? What was the curious trick of lighting that made each picture look like something seen in delirium? When once these questions had been raised the apparent ordinariness of the pictures became their supreme menace—like the ominous surface innocence at the beginning of certain dreams. Every fold of drapery, every piece of architecture, had a meaning one could not grasp but which withered the mind. Compared with these the other, surrealistic, pictures were mere foolery. Long ago Mark had read somewhere of “things of that extreme evil which seem innocent to the uninitiate,” and had wondered what sort of things they might be. Now he felt he knew.

(Apropos of which, no novel is more relevant to our current chaos than Lewis’s magnum opus. Its depiction of the exaltation of evil under the aegis of “science” and “progress” is unsurpassed. If you haven’t read it, I urge you to do so.)

It may be that an argument can be made for such things as art. But how shall we cope with the “withering of the mind” that seems embedded in their essence? Is it a disqualification, or an irrelevance? Indeed, is any characteristic either essential or irrelevant to what we call art? If we cannot agree on such boundaries, how can any discussion of art or artistic qualities enjoy wide concurrence?

The questions Kimball raises are critical in the best sense of that word. They must be addressed seriously: not for art’s sake alone, but to understand what contemporary trends in “art” have done to our culture. Those who are relentless about refusing to define art, or even to agree that some things are irrelevant (if not poisonous) to it, are not friends of Christian-Enlightenment civilization. Their employment of the term art as a kind of benediction that exempts “art” and “artist” from objective judgment is the starkest possible giveaway.

3 comments

I’ve been neglectful at asking you. Have you read as I have that Tolkien advised Lewis not to ever again write anything like That Hideous Strength? And if so, or if you can verify that report, what can you make of it? I, as you, find in that novel a serious fictional presentation of his The Abolition of Man lectures in which I — the non-fictionier — believe contributes even greater value since it opens a window for us to recognize real life monsters.

I cannot imagine why Tolkien so advised his friend — unless he felt it really endangered Lewis. That he died on the same day as JFK and Aldous Huxley always felt like too much of a coincidence.

Author

Tolkien did, apparently, disapprove of That Hideous Strength. (Lewis quipped that he referred to it as “That Hideous Book.”) I’m not sure of the reasons. Perhaps Tolkien would have preferred something more allegorical, rather than Lewis’s direct invocation of supernatural power to thwart the evil of the N.I.C.E. I find the book to be invaluable as a depiction of what comes from allowing men to pose as gods.

It was one thing when art could be freed up from imitating the forms of Nature’s God But even if a work of art is an abstract, all the rules of composition still apply. Proportion, balance, symmetry, completeness, all have to be accounted for. Either the shape is pleasing to the eye, or something about it isn’t right.

But when art divorces itself from beauty, it no longer serves to edify, or even please the eye. It may provoke a reaction, but so does a traffic accident. Contemporary art has removed skill in execution from the prerequisites. Now, a clever idea is enough. And who among us has not had a clever idea? All the barriers for entry into the game are down. Come be a genius! Anyone can do it! Don’t even get me going on ai…

Here’s a link to some of my own works that were rejected for a show compared to the pieces that were awarded prizes. (scroll down a bit)

https://catsofruatha.blogspot.com/2022/11/catching-up-with-stuff.html