Today, over at Cold Fury, there’s an excellent and thought-provoking essay by co-contributor SteveF that explores one of the funnier fallacies commonly advanced as an aphorism:

(NB: I have no idea who Hanlon is or was and bear him no ill will, but I will say that as a vendor of rose-colored glasses, he has few equals.)

Robert A. Heinlein, no slouch in the intellect department, added this codicil:

From here we delve into the real meat of Steve’s essay: system complexity and what its emergence presages.

Steve cites several cases of seemingly inexplicable functional incompetence and addresses them as an engineer would. (Rather than force myself to steal big honking pieces of his essay, I implore you to read the whole thing. It’s worth your time and your full attention, as few of my dollops of crap are.) Here’s his conclusion, as narrowly as I can grab it:

Many systems today are too complex for anyone but a genius to fully understand. Engineered systems, business systems, economic systems, organizational systems. Most systems start simple but as needs change or problems are found they gradually increased in complexity, from something comprehensible by an bright but not outstanding man to a Gordian knot of relationships and dependencies and “don’t change this section; we don’t know why but if you touch it the whole thing breaks”. Others were complex from the start, set up by a genius and then put into the hands of the only-slightly-above-average to operate.

I wouldn’t expect to understand many of those systems in their entirety myself. But I do know how to analyze and explain a failure in a complex system. It nearly always starts with the principles of feedback.

Feedback is the most important principle in practical design. No matter how complex the whole, each of the active or reactive parts must be balanced by a source of feedback that will correct its deviations from planned behavior. A simple example of this arises from the steam engine.

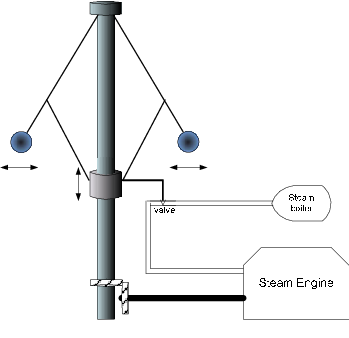

A steam engine will always embed the possibility of a “runaway:” i.e., the rising of the pressure in its boiler to a point that will cause it to explode. Early steam engines lacked a provision for this hazard. The explosions that resulted caused their designers to incorporate what was called a governor: a device that would sense that the pressure of the boiler was rising to a dangerous height and had to be released. Here’s an abstract design for one such:

The pressure generated by the fire in the engine’s boiler rotates the top of the governor assembly. When that rotation reaches a certain speed, the balls pictured will spin fast enough to pull the bottom part of the assembly upward. That uncovers an opening in the pipe through which steam will escape, lowering the boiler pressure. Thus, the source of the potential explosion is used to provide negative feedback that will restrain its behavior to within an acceptable limit.

Systems composed of people must incorporate the same sort of mechanism. Individuals who under-perform, mis-perform, or mal-perform must incur correction in some fashion. The usual problem is that they simply…don’t. When a system combines fallible people with under-designed components of other kinds, the ramifications can exceed even a good designer’s ability to incorporate the necessary feedback mechanisms.

So by looking for the points where the necessary negative feedback was absent, it’s usually possible to figure out what went wrong: why this bridge wasn’t inspected, or that hospital didn’t receive the drugs it needs, or this other bureaucracy didn’t catch on to the fact that Smith had his hand in the till until the scoundrel had fled to Argentina. The great problem is at the design stage…and sad to say, no system can be designed ab initio in such a fashion that later, a posteriori changes – expansion of personnel or accretion of functions not originally intended (a.k.a. “mission creep”) – can’t screw it up beyond recognition.

Bureaucratic systems experience such expansions and accretions with near-perfect predictability. Examples of bureaucracies that haven’t suffered such things are so rare that I can’t name one.

And as usual, that’s not the end of the tale.

Systems of every sort will tend to expand: to acquire more parts and more functions over time. Engineers usually call this retrofitting, when they’re not calling it something profane or obscene. It happens because of the human tendency to avert labor and expense. Doing a whole new design that provides for the “omitted” parts or functions is almost always much more laborious and expensive than jiggering it “just a little bit.” There are other factors, of course, especially in governments. For the analysis of such cases, please refer to the wisdom – really! – of the Great Lawgiver, Cyril Northcote Parkinson.

Every such expansion will multiply the niches in which an opportunist with low motives can cause trouble:

- He might be bent on sabotage,

- Or perhaps peculation,

- And in every case has no real interest in the functions assigned to his position, nor in the system of which he’s a part.

Complexity always favors the machinations of such men. Unfortunately, the dynamic of power, which operates in all bureaucracies, will privilege him above even his superiors in the bureaucracy. They will never possess enough corrective feedback mechanisms or enforcement power to thwart him. Indeed, the odds favor the superiors being denied any information that might evoke corrective reaction. This hearkens back to the SNAFU Principle. In the classic trilogy by Robert Shea and Robert Anton Wilson, Illuminatus, Hagbard Celine expresses it most memorably: “A man with a gun is told only that which people assume will not provoke him to pull the trigger.”

And so an important theorem is revealed:

Therefore, layabouts and villains will seek complexity.

If they can’t find it, they’ll attempt to create it.

I’d call that the FUBAR Theorem, but I’m not sure that epithet hasn’t already been assigned to other uses.

Heady stuff for a Saturday, eh, Gentle Reader? I hate it, myself, as it offers no recipe for corrective action once a bureaucracy is in place. But it’s important information even so. It guides the man who merely wants a place to work at what he does best, unhampered by his surroundings and those who inhabit them.

A coda with which to close: the late, much lamented Ol’ Remus advised us all to stay away from crowds. This is advice of the first water. Crowds are themselves complex entities that facilitate the actions of villains. It hardly matters what particular variety of villainy he intends; whatever it is, a crowd will surely be more favorable for what he intends, and will provide a higher chance for a clean getaway, than a sparse district.

Verbum sat sapienti. And make sure you have enough ammo.