It’s a longstanding conviction of mine, along with Thomas Sowell, that “There are no solutions; there are only trade-offs.” Among its other faults, the Left harps on “solutions” as if it could guarantee the outcomes of its policies. That would be a thrill, wouldn’t it?

The signal characteristic of a solution is that the problem disappears. After all, once it’s been “solved,” there should be no lingering manifestations of it, right? And indeed, that is the attitude of the Left toward just about anything they choose to harp on. However, it’s not perfectly confined to the Left. On certain subjects, the Right has the same attitude.

Let’s start from a frank observation or two:

- People have been using drugs to alter their consciousnesses for centuries.

- The “drug problem” in the United States involves millions of people.

- It also involves many billions of dollars in annual trade.

- It’s been going on since the early Twentieth Century.

I have no skin in this game. I don’t use recreational drugs, unless wine is counted as one. The neighborhood I live in is largely free from any excrescences of the illegal drug trade. But I do have an interest in law and order, in the well-being of Americans, and in American childrens’ futures. That makes the “drug problem” a subject of concern to me.

But I maintain that there is no “solution” to the “drug problem.” No possible change in public policy will eliminate the use of recreational drugs, and I can prove it.

Imagine a totalitarian society, in which enforcers of the Leader’s will are wherever one might look. Imagine that there’s no right of privacy there, that even one’s body is subject to arbitrary search at any moment. Imagine that the movements of everyone confined to that society are also carefully controlled; no resident can do so much as pass through a door without permission and supervision. Imagine that escape from that society is effectively impossible, while ingress is closely and carefully controlled.

Pretty hard to imagine a way to get the drug trade into that society, eh? I mean, how would you go about it? You’d have to corrupt the enforcers, wouldn’t you? You’d have to promise them a piece of the action. Moreover, you’d have to ensure that all drug trade would require their approval.

That is exactly what has happened in America’s prisons. It’s happened to nearly as great an extent to America’s urban police forces. Drug use is utterly rampant in our prisons. Nothing any reform-oriented warden has tried has reduced it. The amounts of money to be made are too great.

The reform wardens and anti-drug zealots will tell you differently, of course. It’s up to you to demand evidence.

We start from there: there is no solution. But there may be a method of amelioration. To find it, we must hold tight to our realism.

A critical insight is required of us. Specifically, we must answer a penetrating question:

What do we really want

From our fight against drug use?

To focus our thinking, we must be utterly candid about what bothers us, whether about drug use or anything else. So let’s list the harms that arise from recreational drugs, as extensively as possible:

- What they do to the user:

- Some drugs are physically addictive.

- Most are also physically harmful to the user.

- They also deflect the user from productive activity.

- Even the least harmful ones can have long-term psychological effects.

- What they do to public institutions and social cohesion:

- The drug trade greatly enriches organized crime.

- It also corrupts many of our politicians and our law enforcers.

- Drug use in the military, though largely undiscussed, is a significant problem.

- The drug trade has a negative effect on our relations with several other countries.

- Family members’ efforts to protect drug-involved relatives degrade respect for the law.

- Other harms:

- Fighting the drug trade costs many billions of dollars per year.

- Drug enforcement is largely responsible for the obscenity called “asset forfeiture.”

- It also compels violations of Americans’ Fourth Amendment rights. (Think “no-knock raid.”)

That’s everything I can think of at the moment. No doubt I’ve omitted something, but perhaps some Gentle Reader will put it in the comments. In any event, I submit that what makes us hostile to recreational drugs are the harms above – and make no mistake: they are considerable. Yet there is no method available by which all the harms can be eliminated.

Discovering an acceptable trade-off might involve accepting that some of the harms cannot be reduced by any means imaginable. Nevertheless, we should try to find a path toward reducing all of them: a path that doesn’t involve still worse harms to individuals or to American society.

Still more realism will be required of us, owing to the longevity of America’s drug problem.

Not many are aware that drug use was first elevated to the status of a problem that needed to be addressed by public policy early in the Twentieth Century. The first federal measure intended to combat drug use arrived in 1914, with the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act:

In the 1800s opiates and cocaine were mostly unregulated drugs. In the 1890s the Sears & Roebuck catalogue, which was distributed to millions of Americans homes, offered a syringe and a small amount of cocaine for $1.50. On the other hand, as early as 1880 some states and localities had already passed laws against smoking opium, at least in public.

At the beginning of the 20th century, cocaine began to be linked to crime. In 1900, the Journal of the American Medical Association published an editorial stating, “Negroes in the South are reported as being addicted to a new form of vice – that of ‘cocaine sniffing’ or the ‘coke habit.'” Some newspapers later claimed cocaine use caused blacks to rape white women and was improving their pistol marksmanship. Chinese immigrants were blamed for importing the opium-smoking habit to the U.S. The 1903 blue-ribbon citizens’ panel, the Committee on the Acquirement of the Drug Habit, concluded, “If the Chinaman cannot get along without his dope we can get along without him.”

[…]

The drafters played on fears of “drug-crazed, sex-mad negroes” and made references to Negroes under the influence of drugs murdering whites, degenerate Mexicans smoking marijuana, and “Chinamen” seducing white women with drugs. Dr. Hamilton Wright, testified at a hearing for the Harrison Act. Wright alleged that drugs made blacks uncontrollable, gave them superhuman powers and caused them to rebel against white authority. Dr. Christopher Koch of the State Pharmacy Board of Pennsylvania testified that “Most of the attacks upon the white women of the South are the direct result of a cocaine-crazed Negro brain”.

Before the Act was passed, on February 8, 1914, The New York Times published an article entitled “Negro Cocaine ‘Fiends’ Are New Southern Menace: Murder and Insanity Increasing Among Lower-Class Blacks” by Edward Huntington Williams, which reported that Southern sheriffs had increased the caliber of their weapons from .32 to .38 to bring down Negroes under the effect of cocaine.

The laws against the importation and sale of the opiates and cocaine were strengthened over the succeeding decades. In 1937, Congress passed the Marihuana Tax Act, which outlawed cannabis-based drugs as well.

From the very first, organized crime seized upon those outlawed substances and became their marketers and source. The major crime organizations were jubilant about the opportunity and the revenue. After the Eighteenth Amendment was repealed, they badly needed the money. That was how drug abuse flowered to become a major subject of public policy in the United States.

While it might not be perfectly obvious, a problem that’s been compounded over a century and more, with ever more people and foreign nations getting involved, isn’t likely to be ameliorated satisfactorily in a year or two. The demand alone makes that an unreasonable expectation.

As long as there are drug abusers, there will be human suffering. That’s indisputable. But it may be possible to reduce the demand over time. Harsh legal penalties have not done so. Indeed, the outlawed status of those highly sought-after drugs is part of the problem: it’s responsible for the prices of those drugs and the crime and corruption they evoke.

How does one reduce the demand for anything? Raising the price sometimes works; so does introducing a superior alternative. And of course, anti-drug education, especially of the young, is critical. Teens who know what drugs such as heroin and cocaine can do to them are less likely to use them. However, I must admit that the arrogance of youth often manifests in the statement that “It won’t happen to me.” A counteractant to that is as yet unknown.

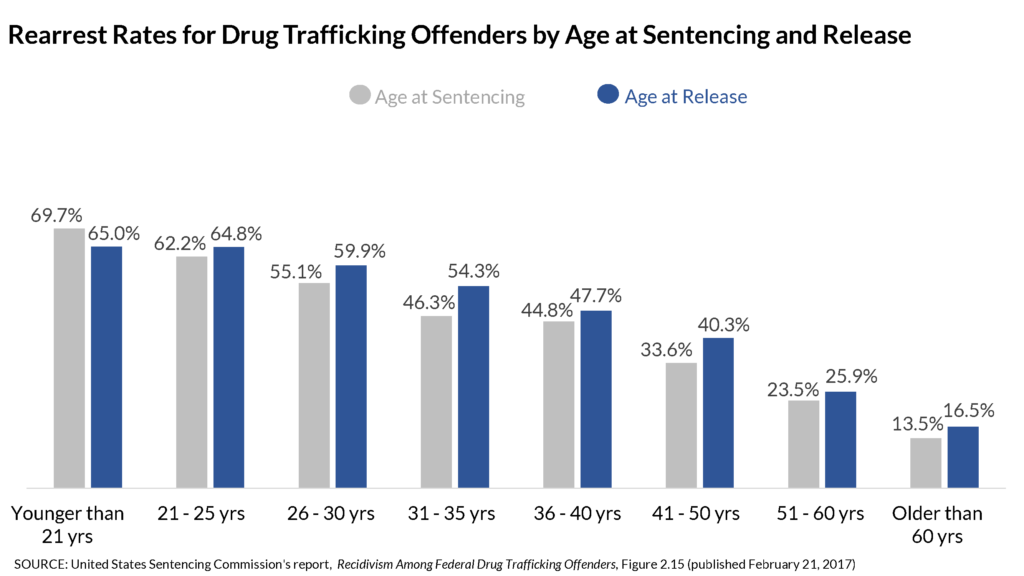

Reducing the demand for a drug among the already addicted is much harder. You could say that the addict lives for his drug of choice. At any rate, he often claims that he can’t live without it. Nor is therapy of any sort particularly effective; the rate of recidivism among users of hard drugs that “get clean” is appalling:

We don’t know how many drug addicts never even try to kick their habits. How could we? Merely admitting to his problem is likely to get the addict incarcerated – another negative effect of the outlawing of those drugs. Add to that the likelihood that relatives will attempt to shield the user from the law, especially if the user is young. That has the unintended consequences of buttressing demand while simultaneously making those well-intentioned relatives lawbreakers themselves, which is an important part of the problem.

As of this moment, there is only one way to reduce the demand for addictive drugs among those already addicted: letting them die. When all the effects are accounted for, the current practice of trying to “help” the drug addict, rather than allowing him to suffer the consequences of his behavior, might be the most harmful thing we do.

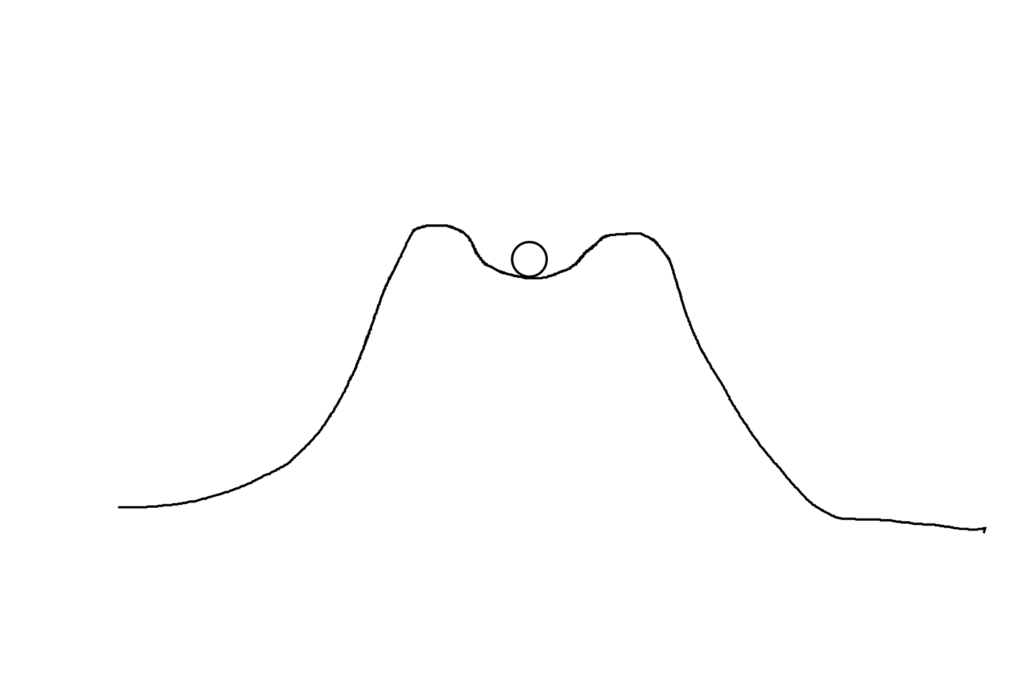

Now for a few words about metastability. Ponder the following simple drawing:

The ball in the depression pictured above is in a gravitationally metastable state. In the absence of any attempt to move it, it will remain where it is. Some attempts to move it will merely disturb it fleetingly; after a moment, it will return to its current position. But a sufficient attempt – one that would push it over the top of one of the bounding humps – would cause it to roll down the hill. In other words, to get the ball to a lower altitude, we must first push it higher.

Metastability is like that. It’s my contention that the drug abuse problem is metastable against any and all proposed counteractions. That metastability arises from the age and size of the problem:

- The size of demand;

- The number of addicts;

- The amounts of money involved;

- The huge amount of official corruption;

- The unwisdom of our attempts to “help” the drug addict;

- Not least of all, our resistance to admitting that we’ve gone in the wrong direction, which is especially strong among public officials and prominent anti-drug activists.

Oregon’s recent decision to recriminalize various drugs was motivated by the metastability of drug abuse. Among other things, merely decriminalizing those drugs was insufficient; see the list immediately above. Even if all the proper measures and repeals had been applied, not enough time had gone by for “the ball” to start “rolling downhill.”

I could be wrong; I’ve been wrong in the past. But so could the “drug warriors,” including my Co-Conspirators. None of us are infallible, and none of us are saints.

If we’re willing to allow that a total “zero it all out” solution is impossible, we can adjust our expectations. Reasonable expectations must incorporate the insistence on measuring the right things. That emphatically means don’t measure inputs. Inputs tell us nothing about harm reduction. Measure instead the rate at which addicts are forming; the amounts of money being spent per capita, the overall level of crime associated with drug abuse, and similar effects.

A few closing words from H. L. Mencken, with regard to another social pathology: prostitution:

There is no half-baked ecclesiastic, bawling in his galvanized-iron temple on a suburban lot, who doesn’t know precisely how it ought to be dealt with. There is no fantoddish old suffragette, sworn to get her revenge on man, who hasn’t a sovereign remedy for it. There is not a shyster of a district attorney, ambitious for higher office, who doesn’t offer to dispose of it in a few weeks, given only enough help from the city editors. And yet, by the same token, there is not a man who has honestly studied it and pondered it, bringing sound information to the business, and understanding of its inner difficulties and a clean and analytical mind, who doesn’t believe and hasn’t stated publicly that it is intrinsically and eternally insoluble. For example, Havelock Ellis. His remedy is simply a denial of all remedies. He admits that the disease is bad, but he shows that the medicine is infinitely worse, and so he proposes going back to the plain disease, and advocates bearing it with philosophy, as we bear colds in the head, marriage, the noises of the city, bad cooking and the certainty of death. Man is inherently vile—but he is never so vile as when he is trying to disguise and deny his vileness. No prostitute was ever so costly to a community as a prowling and obscene vice crusader, or as the dubious legislator or prosecuting officer who jumps at such swine pipe.

Mencken could be speaking directly to us. There are days I wish he could.

4 comments

Skip to comment form

Are you a “Free man” if you do not own your own body? Owning your own body comes with a cost. That cost is personal responsibility. Only folks who own their own body get to decide what to put into it and so must accept responsibility for their actions. Brings a new meaning to “My body, My choice”. Snark!

Many years ago I attended a conference on Counter Narcotics Operations. The cold war had just ended and the military was looking for new wars to remain relevant. Got to maintain those budgets. We were briefed by all federal agencies involved in the “War on Drugs”. I was amazed on how many there were. The last briefer, and the one who made the most sense, was a historian. He graphed drug usage in the United States from the mid 1800’s to current day. The graph showed a roughly 50 year pattern of highs then lows. The graph also showed there were always drug usage. The graph rose when the population accepted drugs and fell when the population rejected them. Lesson: We get what we tolerate and government is not the solution.

Do I think that the 50 year cycle is now broken; Yes. We are constantly bombarded by the pharmaceutical companies that drugs solve all our problems. Hey, we got a pill for that. No worry opioids are not addictive.

I don’t drink, but I’ve been getting high for pretty close to sixty years. It hasn’t killed, or ruined me, cost me a job, or prevented me from graduating college with high honors. As a sculptor I find a little coffee and weed does wonders for the creative process. A lot of people I know function just fine despite being heavy users.

Unfortunately, my adventure with a really viscious strain of the covid last summer wreaked havoc throughout body, and mind. I have breathing problems I never had before, and the mind isn’t as sharp. But I blame the paxlovid for that. It is one nasty drug. Between the bug and the drug I got beaten like rented mule. So I’ve had to part company with the smoke. Haven’t had a toke for darn near a year now, and, truth to tell, I don’t really miss it much. The creative process is back on line, and I’m working on recovering my stamina.

I’ve never done the stuff, but people addicted to heroin can also function just fine as long as they have a steady, affordabe source. I understand it is a very good buzz. If the shot of morphine that I got in the ER is any indication, I can see why people like it. But heroin is dangerous as hell, and I won’t get near it. Everyone who does smack falls in love with it, gets addicted, and eventually goes to the needle. I’ve lost more than a couple of friends that way.

The hallucinogens: LSD, mushrooms, mescaline, DMT are hyped up as being very dangerous. While the effects can be huge and very dramatic they’re really pretty harmless, and no one gets addicted to them.

“What about the guy who takes a sugar cube of acid, and thinks he can fly?”

No. Acid doesn’t work like that. Of course, hallucinogens are a poor choice for a schizophrenic, or a psychotic. But for everyone else, the worst thing that can happen is a very uncomfortable few hours.

But there are some seriously horrible substances: Methamphetamine, PCP (which, thank heavens, has disappeared) and of course, the new kid on the block, fentanyl. I have seen the damage that meth can do, and I don’t need to say anything about Fentanyl. I used to think that people do those drugs because weed was illegal, and often hard to get. I figured if folks could just go to the corner, and buy a joint they wouldn’t go looking for the bad stuff. I was wrong. People are gonna’ do what people do.

My take on it all: Marijuana, psilocybin mushrooms, peyote, and the rest of the hallucinogens should just be legalized. For that matter, throw in heroin and cocaine. I wrote a little about coke a few days ago. The buzz is vastly over rated, and most people do it for a while and then move on. All in all, though, better a legitimate market with some quality and purity standards than bootleg drugs from a criminal underground.

Now, of course, I’m generalizing. And, of couse, there are people who will ride the dragon all the way to ruination and death. But those folks will ride that dragon even if it comes in a 16 ounce can. Consider that in Africa, those who can’t get anything else do jenkum. (don’t look it up if you’ve eaten recently)

JWM

Francis I don’t have the “answers” to the drug problem. I do know that making it illegal and forcing obtaining them more difficult has not slowed this scourge one whit. In fact it may have exacerbated the problem. When you prohibit something the curious will be curious. Addictive drugs are not limited to opiates – no no, the poison big pharma produces can be and ARE even more insidious.

Case in point – Alprazolam (Xanax) is a benzodiazepine and a potent tranquilizer. It has been prescribed for decades for anxiety and was “effective” when taken as directed. As with most such drugs the human being taking them develops a tolerance and requires a higher dose to maintain the status quo. The vicious cycle continues ad nauseum. By government dictates doctors are now required to wean patients off the higher dosages of this poison. I say poison because if enough is taken death can and likely WILL result. When I did my stint at a mental hospital for my Pharmacy Tech license this was one of the most prescribed meds in the Pyxis (med distribution machine). I know people who feel they cannot get along without this – and indeed develop more anxiety at this thought. Drugs are a self-sustaining entity. Take them, use them, abuse them and wean off, take them, abuse them ad nauseum.

I wish I had a real answer, I truly do. Oregon has proven that making them legal does not work either. Perhaps we are “overmedicated” and have been made to believe that drugs can fix all of our maladies and conditions. This perception (or lie if you will) must be eliminated from the culture. Of course this is all just horseshit and in many cases the poison IS the problem.

Author

I beg to differ, George. Reread the essay, and give special attention to the portion on metastability.

“Proof” is not the same as “we stuck a toe in the water and didn’t like the temperature.”