“I said it as soon as I got to Elbow: I’m a free man, I didn’t have to come here! . . . We always think it, and say it, but we don’t do it. We keep our initiative tucked away safe in our mind, like a room where we can come and say, ‘I don’t have to do anything, I make my own choices, I’m free.’ And then we leave the little room in our mind, and go where PDC posts us, and stay till we’re reposted.”

[Ursula Le Guin, The Dispossessed]

Some days it seems irrefutable that there’s an “oceanic subconscious” that strives to inject particular ideas into all of us. On such occasions, the more insightful and articulate express them clearly for the rest of us. We lesser ones mostly just nod. A few of the brighter dimbulbs might mutter “of course” or “now tell me something I don’t know.”

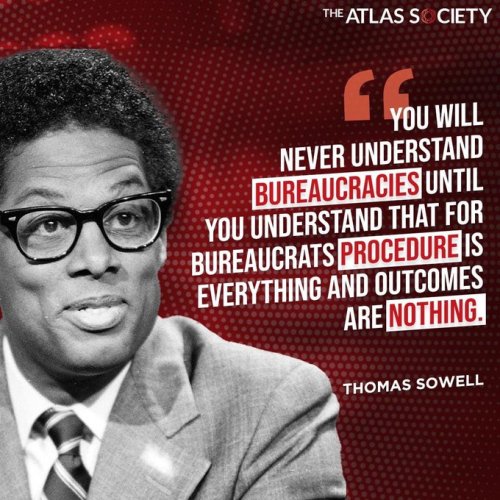

For several decades, the ranks of the insightful and articulate have been headlined by Thomas Sowell:

It immediately made me think of this recent essay at American Greatness:

A cog, they tell us, is a motion-transferring wheel with sprockets along its edge. A collection of them, engineered and assembled, as in a Swiss watch, can be so beautiful to behold that some designers have taken to leaving the whole assembly visible to the eye. It’s reassuring to ponder such precision, to know the mere tightening of a spring can set an army of brass and steel parts off to work in lock step.

But when we describe human beings as mere “cogs in a machine,” we might want to reconsider the horror that could represent. A well-designed machine can signal a reminder for your daughter’s piano recital or it can efficiently grind human flesh to paste. “Cog in a machine” is a different version of the Nuremberg defense. “I was a sprocket on a wheel, doing what sprockets do, taking orders.”

Horror? Well, perhaps, at least in specific circumstances such as the ones writer James Patrick Riley details. But concentrating on one’s nightmares could put us fatally off our slumbers. There are attractions to what I think of as “the cogly life.” Indeed, for the majority of us that mode of existence might be inescapable. To be nudged – or shocked – out of it might be the greatest of calamities.

There’s a great, classic story by Russian writer Nikolai Gogol titled “The Overcoat,” whose main character is a cog: a functionary named Akaky Akakievich Bashmachkin. It’s been anthologized many times, so perhaps my Gentle Readers are familiar with it. The core of Akaky’s character is indisputably cogly:

It would hardly be possible to find a man who lived so much in his work. It is not enough to say he served zealously — no, he served with love. There, in that copying, he saw some varied and pleasant world of his own. Delight showed in his face; certain letters were his favorites, and when he came to one of them, he was beside himself: he chuckled and winked and helped out with his lips, so that it seemed one could read on his face every letter his pen traced. If his zeal had been rewarded correspondingly, he might, to his own amazement, have gone as far as state councillor; yet his reward, as his witty comrades put it, was a feather in his hat and hemorrhoids where he sat. However, it was impossible to say he went entirely unnoticed. One director, being a kindly man and wishing to reward him for long service, ordered that he be given something more important than the usual copying — namely, he was told to change an already existing document into a letter to another institution; the matter consisted merely in changing the heading and changing some verbs from first to third person. This was such a task for him that he got all in a sweat, rubbed his forehead, and finally said, “No, better let me copy something.” After that he was left copying forever.

Yet the story is far more memorable than one might expect from a tale about a cog. Akaky becomes aware that a vital component in his routine must be altered: specifically, his overcoat, which has become incapable of preserving him against the frosty Saint Petersburg weather. But his tailor Petrovich informs him, somewhat sadly, that to repair the old garment is not possible; it has suffered nobly but too long, and will not accept further patching:

Petrovich took the housecoat, laid it out on the table first, examined it for a long time, shook his head, and reached his hand out to the windowsill to get his round snuffbox with the portrait of some general on it — which one is not known, because the place where the face was had been poked through by a finger and then pasted over with a rectangular piece of paper. Having taken a pinch, Petrovich stretched the housecoat on his hands and examined it against the light and again shook his head. Then he turned it inside out and shook his head once more, once more opened the lid with the general pasted over with paper, and, having filled his nose with snuff, closed the box, put it away, and finally said:

“No, impossible to fix it — bad wardrobe.”

At these words, Akaky Akakievich’s heart missed a beat.

“Why impossible, Petrovich?” he said, almost in a child’s pleading voice. “It’s only a bit worn on the shoulders — surely you have some little scraps. . .”

“Little scraps might be found, we might find some little scraps,” said Petrovich, “but it’s impossible to sew them on — the stuff’s quite rotten, touch it with a needle and it falls apart.”

“Falls apart, and you patch it over.”

“But there’s nothing to put a patch on, nothing for it to hold to, it’s too worn out. They pass it off as broadcloth, but the wind blows and it flies to pieces.”

“Well, you can make it hold. Otherwise, really, it’s sort of. . . !”

“No,” Petrovich said resolutely, “it’s impossible to do anything. The stuff’s no good. You’d better make yourself foot cloths out of it when the winter cold comes, because socks don’t keep you warm. It’s Germans invented them so as to earn more money for themselves.” (Petrovich liked needling the Germans on occasion.) “And it appears you’ll have to have a new overcoat made.”

This disturbance of Akaky’s previously undisturbed rotation around his life’s axle shocks him out of his usual habits of thought. Rather than spoil the story for you, I’ll say only this: Akaky’s departure from cogdom, even in this seemingly small matter of a new overcoat, has unfortunate consequences – and not just for him. They spiral outward to disturb the rotation of cogs of even higher place.

Gogol’s story might be taken as merely a horror story of that unique Russian variety in which desolation and loss are inevitable. However, his tale extends to other themes. It functions as well as a sermonette on what can come of even microscopic disturbances to the Great Machine as on anything else.

Cogs don’t spin themselves; some motor of independent force must propel them. But what spins the motors? Initiative? Ambition? Hunger? It varies. In bureaucracies of the sort that characterized Russian life both before the Revolution and since then, a great many cogs spin obediently to the orders of persons so highly placed that the very thought of them induces terror and an immediate recourse to the unconsciousness of routine. Routine, after all, is safe. Its rhythms are known, regular, soothing. They prevent the intrusion of unwarranted thoughts. Besides, routine is the center of existence for a cog. Should he cease to spin or lose too many teeth to function, he would swiftly be pulled and replaced, for the Machine must be kept running. Any other course is unthinkable – perhaps literally.

American society has been filling up with cogs since industrialization and urbanization took hold on these shores. Men whose fathers had to think, decide, and act consciously to stay alive have been steadily replaced – perhaps displaced would be a better word – by what were once called organization men: bureaucrats; men in gray flannel suits; cogs.

As the cogs have multiplied, the men of independent vision, thought, and will have become ever more visible and valuable. We transform some of them into champions of a sort. The Eighties’ great surge of interest in entrepreneurship was less a response to the appreciation of the virtues of free market capitalism than a response to old-fashioned hero worship. The difference was in the selection of heroes.

No one actually aspires to be a cog. Most of us have great dreams, at least before we’ve collided head-on with the realities of life. But cogdom eventually absorbs most of us. While we spin smoothly and without untoward demands for lubrication, we manage to live. Some of us even manage to live well.

But every now and then recognition sets in. A cog becomes too conscious of what he has become to remain comfortable on his axle. He speaks up. Perhaps he acts out.

And all too often, the other cogs, moved by a subconscious awareness of danger, descend on him in a body and remove him from the Great Machine. Few if any of them could say why. They know they must act; to do nothing in the face of deviance is to risk consequences too terrible to envision.

The Machine, after all, must be kept running.

3 comments

Hmmm. Why do the good die young? Mercy!

I don’t know of another living man as brilliant and as unappreciated, especially by those who style themselves his people, as DR Sowell.

“A cog, they tell us, is a motion-transferring wheel with sprockets along its edge.”

No, no, blast it, NO! A COG is a GEAR is a SPROCKET, which has TEETH along its edge. It’s a good article, don’t know why that got under my skin so deeply when I first read the thing.

MAAAAATLOCK!!! Umm, sorry, all.