One of the little tricks by which the Left has made steady inroads into American life is the effacement of important distinctions. While this is largely a matter of linguistic chicanery, its effects often eclipse those of any other political tactic. That makes it an important front in our political combats.

Unfortunately, many intelligent and benevolent persons unwittingly assist the Left in this regard. They do so by failing to exercise adequate penetration into the issue under discussion.

Yes, I have an example in mind. But it will take more coffee to address it adequately.

Have a snippet from John Wilder’s latest:

I can take a $100 bill and go and buy some beer and cigars and PEZ®. I could also do that with a gun, but the fact that everyone will go along with the deal means that the dollar really is money.

John has effaced an important distinction indeed.

Before I proceed, allow me another snippet: this one from the first edition of Dreams Come Due: Government and Economics As If Freedom Mattered:

Money: A medium of exchange and a store of value.

The greatest fraud and confusion perpetrated by governments has been the substitution of unbacked currency for money. People now believe that currency is money. Nothing could be further from the truth.

There can be no compromise to the definition of money. Many things can have one of the traits of money. Currency is a medium of exchange and land can be a store of value, but neither one is money, especially currency, because no currency in history (not one) has ever retained its value. There is no currency in the world today (including the Swiss franc) that is not losing purchasing power every year.

In his snippet, John has described the “medium of exchange” function of money, which currency, a substitute for money, can fulfill. But owing to inflation, a government-controlled process I’ll delineate at a later time, the $100 Federal Reserve Note of which he speaks has far less purchasing power today than it did at any previous point in history. Thus, it fails to perform the “store of value” function of money.

The first question I usually get when I present the above distinction to a class goes roughly thus: “Well, why did the shopkeeper accept the $100 bill if it isn’t money?”

There are two reasons, above all others. First, anyone in a retail business would intend to replace the goods he’d just sold for that $100 bill – and the retailer’s vendors would, in exchange for that $100 bill, ship him more goods to sell. Of course, that merely begs the question by transferring it to those notional vendors. Why would they accept the $100 bill for the goods they ship?

The answer appears in the corner of every Federal Reserve Note ever printed:

THIS NOTE IS LEGAL TENDER

FOR ALL DEBTS, PUBLIC AND PRIVATE.

Pull one out of your wallet and look. It’s in very small font, but I guarantee that it’s there. Use a magnifying glass if you must; you’ll find it.

The “legal tender” provisions of the Federal Reserve Act make the acceptance of such notes legally mandatory. No one who sells his wares for prices denominated in dollars is permitted to refuse them. It’s a federal offense. Never mind that in recent years the Treasury Department has at times declined to enforce that law.

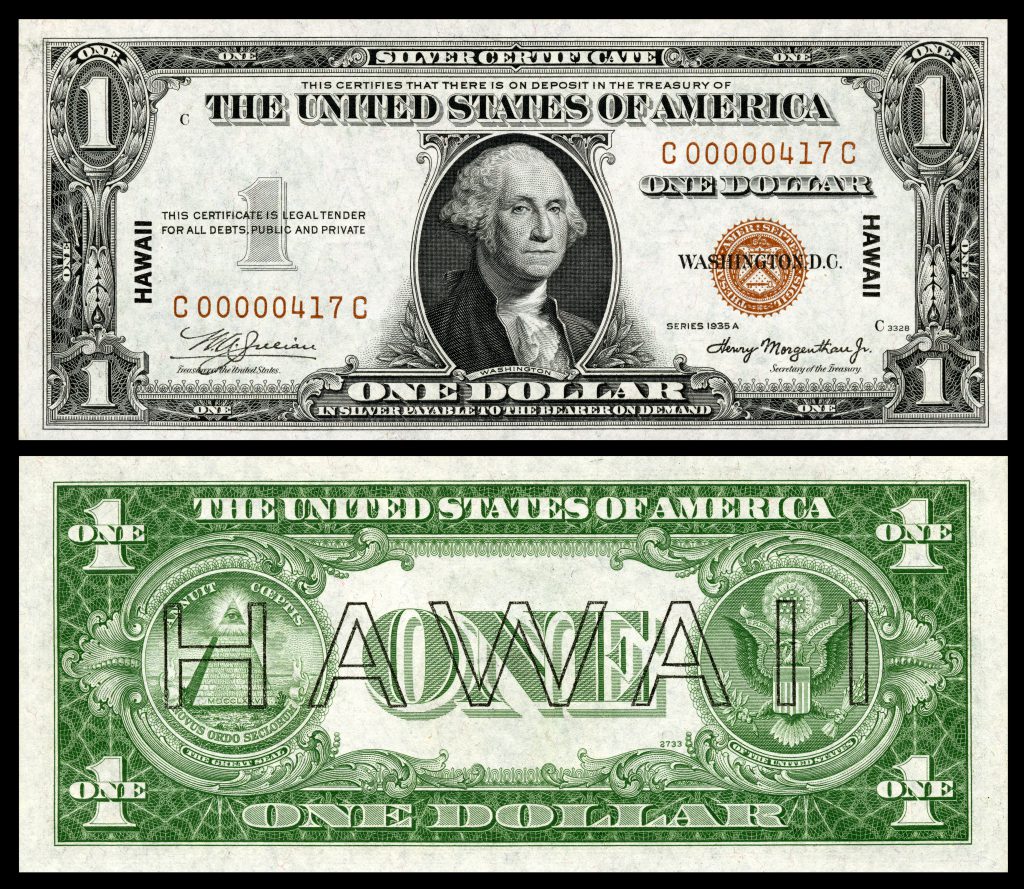

If you have one of the older notes that, instead of “Federal Reserve Note,” says “Silver Certificate” at the top, you’ll find much different verbiage on it. That’s because until 1968, the law mandated that any bank in the Federal Reserve system was legally required to give you a silver dollar for it, should you demand it. The Treasury stopped printing Silver Certificates in 1964. Here’s an image:

Incidentally, if you have any silver coins – actual silver, not the cupronickel sandwich coins imposed upon us since 1969 – you should store them somewhere safe. There’s quite a market for such coins, as they’re worth considerably more than their face value in dollars. So the distinction between money and currency matters very much. It must never, ever be effaced.

The above is just one example, a current one of particular interest to me. There are many others. Consider the federal debt as an example. Recently, an elected cretin strove to efface the distinction between payable debts – the sort you and I routinely accumulate on our credit cards, which the law will enforce upon us should we seek to evade payment – and bad debts: the sort which will never be paid, because they’re owed by governments which will not enforce collection upon themselves. Quoth Murray Rothbard:

If the government has incurred a huge public debt which must be paid by taxing one group on behalf of another, this reality of burden is conveniently obscured by blithely saying that “we owe it to ourselves” (but who are the “we” and who the “ourselves”?).

In point of fact, the phrase “we owe it to ourselves” has fallen into desuetude, because the public is generally aware that “we” don’t owe it to “ourselves.” Federal debt instruments – T-Bills, mostly – are now owned principally by the Federal Reserve Bank and by foreign governments. Moreover, the interest on that debt is paid out of tax revenues: funds collected under threat of punishment from private persons and institutions. Call me naive if you like, but I see certain problems in taxing myself to pay myself, which I why I don’t own any T-Bills or Savings Bonds.

Clearly, the distinction between payable debts and bad debts matters quite a lot.

I could go on, and sometimes I do. Critical distinctions matter. When you hear someone say “Oh, that’s a distinction without a difference,” put one hand on your wallet, the other on your sidearm, and back slowly away, never taking your eyes off him. More often than not, the speaker will be trying to obscure a critical distinction, in the interest of some rapacious scheme he seeks to advance. While that’s not the case with John Wilder, it’s as important for good persons not to collaborate in the destruction of such distinctions as it is for us to be aware of attempts to do so.

See also this vital Baseline Essay on the nature of money and currency.

10 comments

Skip to comment form

When I was a wet behind the ears 2nd Lt., I was assigned the duty to collect US Savings Bonds pledges on base. My selling point, suggested by a savvy Captain, was “Put your money in a sure thing. Invest in deficit spending.” Didn’t get many pledges.

Now that you recognize the distinctions regarding “money”, realize that a Silver Dollar is a “dollar”, and a FRN is not. Read the Seventh Amendment with this understanding.

One minor correction: The copper-nickel sandwiches that replaced US silver coins began in 1965, not 1969. The last year in which dimes and quarters were made of silver (Troy, 90%) was 1964. If I’m not mistaken, there was a silver Kennedy half dollar minted in 1965.

The copper-nickel sandwiches were known as “Johnson slugs” because the minting of them began in the Johnson administration.

They are, at the moment, worth more than twenty times their face value. If you take a roll of 40 quarters minted in 1964 to a local silver dealer, he’ll probably give you around $210 in Federal reserve notes.

The older silver coins can have additional numismatic value, depending on their condition. But even for the rare ones, the value of the silver — what they call the “melt value” — is generally the largest portion of their value.

You are making a distinction without a difference. Gold and paper money are the same, as each only has value if people believe they have value. There is nothing intrinsically valuable about gold, or anything else. It is all an illusion that only exists within peoples’ minds. Saying paper money has value because it is backed by gold is just 2 levels of illusion stacked on top of each other, which only makes 1 illusion easier to believe.

Author

Nonsense on stilts. People have always valued gold, just as they’ve always valued diamonds and other rare and beautiful things. Alongside that, gold and silver have intrinsic properties that make them useful, though some of those uses were only discovered recently in historical terms. Tell me about why people value paper with numbers printed on it. Better yet, tell me about why people voluntarily and spontaneously adopted gold and silver as monetary media rather than printed paper, and had to be forced to give them up.

Liberty’s Torch and its readers are the major leagues. Nonsense is generally held in contempt, especially on important subjects — and while we’re on the subject of important subjects, we have the separate words distinction and difference for a reason. Think about it.

Sold ALL my US Savings Bonds when the jug-eared half-breed was selected to occupy the Oval Orifice (2008). Used the proceeds to buy “junk” silver, which has increased in value significantly since then.

Minor correction on legal tender: If you offer notes and coins, which have been declared to be legal tender, in payment of a debt, the debtee is not required to take it but he cannot then say that you didn’t offer to pay. You still owe the debt but the other guy can’t get you arrested for running out on it. (That is, if the cops and judges understand and honestly enforce the law, not a safe bet.)

This topic caused a ruckus in my first year Contract Law class when it came up, with half of the class (sponge-headed wanna-be world changers) arguing about how the world should be while the other half of the class (small business owners, mainly) mostly kept quiet but put in a word or two about the realities of life when you’re the one signing the paychecks and not the one complaining about not being able to use the EBT card to buy beer. The professor eventually shut everyone up and got back to the syllabus but it was a fun few minutes.

Author

Interesting. I know for certain that legal tender must be accepted by any government, in payment of a governmentally-imposed obligation. That’s part of the mechanism that obstructs “debtor’s prisons,” and other antediluvian mechanisms. But I’m surprised to hear that if you owe a monetary debt, your creditor can refuse to accept payment in legal tender. Are you perfectly sure about that?

I know that there is at least one condition imposed on the use of legal tender: You cannot insist that your creditor accept payment in “unreasonable” denominations: e.g., paying a debt in the hundreds of dollars with a sack of pennies. But beyond that?

It is a widely held belief that U.S. law requires that businesses accept cash payments from their customers. Some people take the argument a step further, arguing that if a business refuses to accept cash from a customer, the business loses its ability to charge the customer. Neither belief is true.

Paper currency in the United States is printed with the provision that it is “legal tender for all debts, public and private”, language that flows from the provisions of a federal law, 31 U.S.C. Sec. 5103,

Federal law does not prevent a private business from developing its own payment policies and procedures, including policies that restrict or reject payments in cash. For example, a business may require that payment be made by credit card, may require check or money order, may have a policy against accepting large bills, or may combine restrictions of that nature when creating a payment policy.

Although it is possible to find an occasional case that suggests that a unit of state or local government is obligated to accept cash payments, there are in fact no cases that expressly hold that such an obligation exists.

Absent a law that specifically imposes a consequence on a payee for refusing cash, a refusal to accept cash will not impair the payee’s right or ability to collect a debt.

https://www.expertlaw.com/library/consumer-protection/it-legal-refuse-cash-payment

Francis, it seems that the law is between what you thought it was and what I thought it was. (Which leaves me baffled. How could I — I — have been wrong? Could my Contract Law professor have said it wrong? Could the law have changed? Surely I could not have misremembered???) For an existing debt, the debtee is required to accept legal tender which is offered, though sellers may set policies on what denominations they’ll accept. Sellers are in a different position because they are in a position to refuse the legal tender before the sale is made — they are not debtees or creditors until the purchase is made, and the purchase is not made until the payment is accepted; legal tender laws do not apply. That’s US federal law. States may impose deeper demands, though I didn’t see anything other than fiddling with the details in the little research I did.

Divemedic’s linked article is on point and seems accurate, though note that a number of other authoritative-sounding articles differ in details.